Modern art. When shown to a student of the classics, these words may fill him with despair. Whatever happened, he will ask, to the beauty that came through the great artists like Michelangelo and Rembrandt? The artist will weep, lamenting the bygone days where an artist needn’t sacrifice beauty in order to survive in a modern world. The he will mourn for the times when art depicted something, anything, and was actually intelligible.

If this is how the student responds, however, he will have made a grave mistake. While not always, abstract art can be meant to depict something intangible.

Let us say that an you want to draw the concept of hope. How would you go about depicting hope? You could depict a scene with hopeful people. You could depict a scene were people are fighting, struggling for their freedom against all odds, knowing that they will not win but hoping that their message will live on. The soldiers know that they will not survive the battle, but they hope that one day their side will prevail and their children will know the freedom they are striving for.

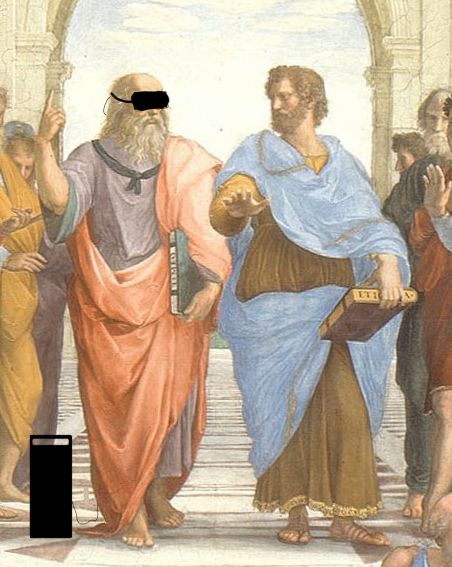

This is one way of trying to depict hope, but this isn’t really depicting hope. Yes, it is depicting hopeful people, but this is different from depicting hope. It’s the same point Socrates brings up in the Meno: “Suppose that I […] ask of you, What is the nature of the bee? and you answer that there are many kinds of bees”. While an individual example of hope has been painted, hope itself has not yet been shown.

While hope could be personified and shown as a person, again this is not a real depiction of hope. Hope is not a person; hope is a concept, an idea. While hope could be depicted in this way, it would not be an accurate depiction.

Thus, hope cannot be depicted in a traditional way. While the intangible concept of hope cannot be physically depicted on a canvas, perhaps the best way to depict hope, an abstract concept, would be through art which is itself abstract. As Michel Henry says in regards to Wassily Kandinsky, “[…] the abstract content that painting seeks to represent is ultimately a content entirely foreign to the world“.

Thus, abstract art seems unintelligible because it is trying to make tangible an intangible concept. While this by no means makes out abstract art as beautiful, it at least shows that the art is not always completely meaningless.

If you’re interested in more content like this, feel free to subscribe to my blog, The Codegito!

Sources:

- Seeing the Invisible: on Kandinsky by Michel Henry, page 21. ISBN 978-1-84706-447-9

- Inspired by this blog post

You must be logged in to post a comment.